SILVER NITRATE

This is a project I did that I developed from a suggestion to take intuitive photographs. I could not conceive of an honest way of being intuitive with a camera unless I was without eyesight. Maybe at the beginning, when I first picked up a camera, and before I was familiar with the elements that made up a photograph, it could be conceived that intuition was being used to take pictures. But after an education and years of contemplation of photographing, my eyes became very selective.

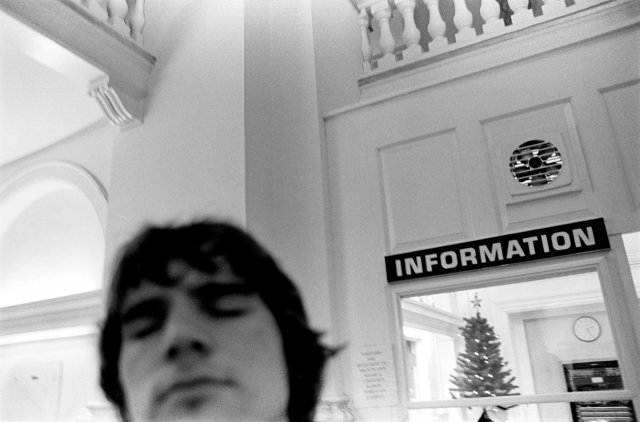

This idea of being without sight became the driving force behind this work. I felt that by giving up my eyesight I was getting back to that beginning period of a photographers journey when all is new and fresh. I discarded all that I had been trained in, letting all considerations of composition and light go, subjecting myself to the subject matter and the decisive moment in which to take a picture.

I began by giving myself a rule to follow to keep the projects integrity intact. The rule was I couldn't have previously seen any of the things I was going to shoot. I felt any familiarity would hinder the idea that I had no prior notion to what any person, place or thing looked like. I wanted the camera merely to act as a device that would replace my eyesight for the duration of time I was photographing my subject matter. It was also at this time that I realized I would not be able to see any of the things I had encountered until after developing the images from the shoot.

I decided to let go of the cameras control functions as well. I simply put the camera on a fully automatic functionality, and hoped that it would do its job as a reliable tool. This would allow me to focus on the decisive moment of taking the picture that was now triggered by my remaining senses.

Next was defining a subject matter that had more relevance to the conceptual element of the project. I thought that the relationship of being without sight while photographing, and photographing individuals who are visually impaired, would be an interesting starting point of conversation for myself and my subjects. I began by researching schools for the blind in the Philadelphia area and upon my first inquiry I found Overbrook School for the Blind and Lucy Boyle. This was a place I had never been, full of people I had never met, and of which had an interesting vantage point.

With the project now underway I had more to consider. I had a time scheduled to drive up to the school, walk up to the door, close my eyes and walk in without sight. I would spend four hours with Lucy in the school, and then leave with my exposures, never seeing any of the contents within the building until developing the photographs I had taken.

What I hadn't contemplated was how I was going to stay without sight. Prior to the shoot date I decided that instead of wearing a blindfold, I would simply keep my eyes closed. I felt that in doing this, it showed dedication to the idea driving the project. I also felt it offered a better sign of respect to those that I would encounter and who had no choice of their visual impairments.

At the end of the day, I was still a sighted individual exploring an idea within a photographic realm. However, incorporating Lucy as my main subject brought a new problem for me to solve. The problem was that her and I would be sharing an experience together that I would eventually turn into a product that she did not have a way of experiencing with her own senses. I felt this was unfair and began to investigate a resolution to this problem.

I conceived that if I could place braille on the surface of the images that were taken, I could give her my direct interpretation of the images through my own words. By placing the braille directly on the images, I was now giving her direct access to the artwork through her own means of interpretation like a sighted person that would view the photos. By choosing not to translate the braille into written words for the sighted, the sighted now became dependent of those who could read braille, making the sighted and visually impaired dependent on each other.

The Associated Services for the Blind was conveniently located in Philadelphia and willing to help me in this task. They allowed me to make Braille press plates that I could emboss inkjet photo paper with. This would give me the raised Braille characters I needed on the surface of the photographs.

The processes, rules, ideas, and concepts were all now defined. I went to Overbrook and spent four and a half hours talking with Lucy and photographing. It was an invigorating experience for me of which I will never forget. Lucy was a wonderful lady and made the project more than just a photographic exploration. I am forever indebted to her for her compassion to allow me to work with her, and for her to be such a courageous and wonderful women.

Lucy was born with sight, but was blinded by an overdose of silver nitrate drops that were given to newborns to help clean their eyes at birth. Prior to the day of photographing, I had decided that I would only use black & white film. This is a process that uses silver nitrate as a key element to make the photographs possible. How coincidental that the thing that had taken her sight, would now be the primary element that allowed me to see her for the first time.

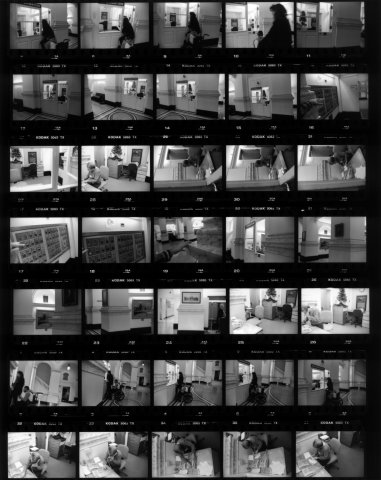

These are some shots of the exhibition with Lucy reading braille to some viewers, individual images from the day, and all of the contact sheets that were taken of that day.